The great Russian physicist and Nobel laureate Lev Landau once remarked that “cosmologists are often in error, but never in doubt”. In studying the history of the universe itself, there is always a chance that we have got it all wrong, but we never let this stand in the way of our inquiries.

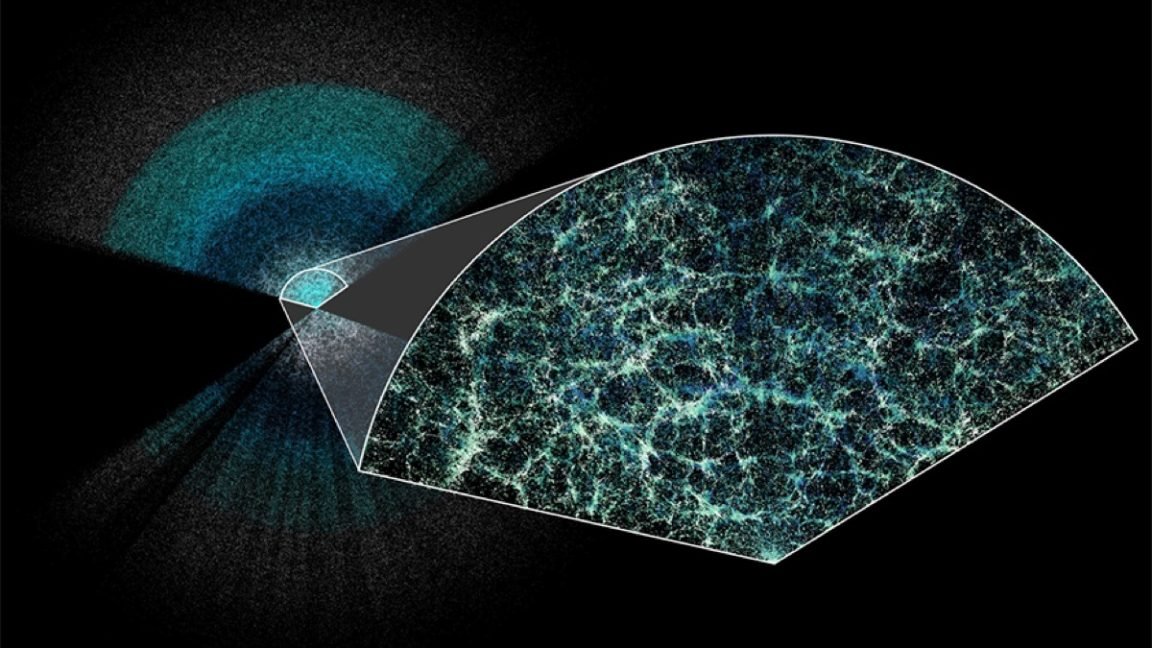

A few days ago, a new press release announced groundbreaking findings from the Dark Energy Spectroscopy Instrument (DESI), which is installed on the Mayall Telescope in Arizona. This vast survey, containing the positions of 15 million galaxies, constitutes the largest three-dimensional mapping of the universe to date. For context, the light from the most remote galaxies recorded in the DESI catalogue was emitted 11 billion years ago, when the universe was about a fifth of its current age.

DESI researchers studied a feature in the distribution of galaxies that astronomers call “baryon acoustic oscillations”. By comparing it to observations of the very early universe and supernovae, they have been able to suggest that dark energy – the mysterious force propelling our universe’s expansion – is not constant throughout the history of the universe.

An optimistic take on the situation is that sooner or later the nature of dark matter and dark energy will be discovered. The first glimpses of DESI’s results offer at least a small sliver of hope of achieving this.

However, that might not happen. We might search and make no headway in understanding the situation. If that happens, we would need to rethink not just our research, but the study of cosmology itself. We would need to find an entirely new cosmological model, one that works as well as our current one but that also explains this discrepancy. Needless to say, it would be a tall order.

To many who are interested in science this is an exciting, potentially revolutionary prospect. However, this kind of reinvention of cosmology, and indeed all of science, is not new, as argued in the 2023 book The Reinvention of Science.